Blurring Boundaries: An Interview with CREW

“Our whole reality is already layered. It’s already a science fiction type of reality.”

[RESIDENCY] CREW is a pioneer collective based in Brussels, specialized in constructing and interrogating wide immersive forms, mixing performance and technology in large scale areas. As part of Realities In Transition, they were mentoring the second residency of the European program – with the selected artist Letta Shtohryn –– which took place at our partner’s venue: iMAL – Art Center for digital cultures & technology, where they’ve been experimenting for a while. Dark Euphoria asked them about their relationship to XR, their favorite tools+inspirations and the different resources they shared during the residency…

Dark Euphoria | Interviewer: Céline Delatte

Glad to finally be able to meet the three of you, Eric, Istjar and Haryo! Thanks for accepting this interview as you finished the collaboration with Letta Shtohryn on her project “Чули? Чули”. To begin, could you give me a quick word to introduce your collective?

Eric Joris: We are a small collective of artists, technologists and scientists, active mainly in XR + VR. Our background is theater, which explains the performative nature of everything we do. We like to develop the tools that we feel are necessary to push the medium.

C.D.: How would you actually define extended realities?

Isjtar Vandebroeck: There are a lot of discussions about this. The original term actually comes from virtual production because it was “set extension”, so you have your camera, you have your real world scene and then you have your set extension with projectors or LED walls. Apparently the name comes from there. Generally people were looking for a name which can kind of group together the different types of alternate realities such as VR, AR, MR… Such definitions, except the one for VR, tend to change all the time. At some point it was spatial computing, a term from a while ago, which Apple is picking back up. The nomenclature and the different types of definitions are all the time in flux but for us it doesn’t really matter. We tend to speak about immersive technologies. Now it is XR so we use XR because that’s what people understand, but it does make it a bit complicated because many people have no idea what XR really is. It’s a porte-manteau world for AR, VR and MR, but even the definition between AR and MR also changes all the time so it’s not very clear…

Eric Joris: What we do is mostly what used to be called in the recent past “mixed reality”.

C.D.: What term do you actually use to describe what you do?

Isjtar Vandebroeck: I think our main effort is in VR and we just use the term VR generally, but then we kind of take the idea of XR to actually extend the VR in a way into scenography and things like that. This is the way we’re working right now, I think.

Isjtar Vandebroeck: I’m working on a new one: “fragmented realities”.

C.D.: This is definitely a pertinent one… As immersive performance pioneers, how did you actually meet XR? And how has it evolved since then?

Eric Joris: We made a performance with a paraplegic performer (‘Philoctetes’, 2002), and we needed to develop tools for him so that he could handle a robotic arm/leg that was like an extension of his body. That ‘prosthetic’ concept we took later to the VR medium. Could the audience be where the paralysed actor was, inside the machine so to speak? Virtual reality did exist at that moment, but you needed big and expensive equipment like Onyx Computers and very heavy headsets ….

We had the chance to work with the University of Hasselt with a brilliant engineer, Philippe Bekaert. We developed a different type of VR, one that we could take on stage. It was video based and could perform many things the digital variant was not capable of. Philippe built nearly everything from scratch: 360° camera’s, code for live stiching and streaming, a tracking system. The biggest problem however proved to be the use of this new medium in relation to an audience: how to communicate, tell, act ourselves, and how to make the audience experience, understand, and interact…? The limitations of our configuration forced us to come up with solutions that we use up till this day.

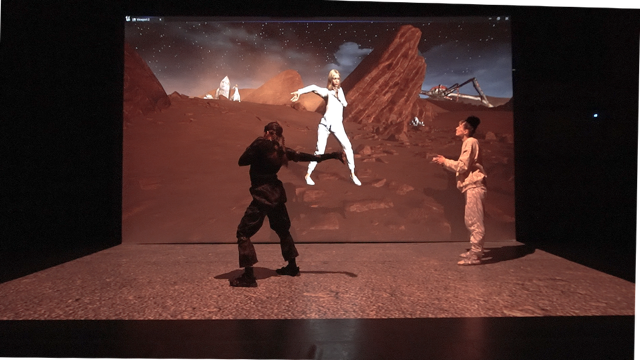

In 2014-15 approximately, we moved back into the 3D digital version of virtual reality, at that moment still very much a ‘seated’ thing, mostly limited by the tracked area. Again, we tried to have things moving which is still the basis of the work we do.

Isjtar Vandebroeck: There’s an important aspect which is still continuing in the way that we work. From the beginning, there is like a mix of what is going on live and these type of things, which is very atypical because from an industry point of view, XR was always approached from: “you have something at home, you download something at home, whether it’s a movie or something like this” and it was not at all conceived as a theater or a performance type of thing.

And we continue working in this way and this continues to be a friction in the field, because the investments go in one direction and we think we have to develop it in another direction. Recently, with the XR-thing and location based experiences, we are kind of proud that our vision, even if it is sometimes in a commercial and kind of tacky way, is taking more form in this way.

Eric Joris: An important advantage that we had/still have, is the working together with researchers, not only technologists but also art- and media philosophers, neurologists, psychophysicists,…: what does our medium and our senses and mind produce in terms of understanding on what’s around you, the world, your own, your self, your body, …? We came to understand VR as a transitional medium: it could well create strong illusions, but half of its existence lies anchored in the real and physical world. Unlike cinema you are transitioning in between two realities. Your agency in this ‘in between’ state is the most interesting and outstanding aspect of VR, and precisely because of that it is also the most difficult to handle from the point of view of the maker, director, artist.

C.D.: What are your favorite XR tools? The specific tools you like to use in order to build your experiences?

Isjtar Vandebroeck: When I arrived at CREW, they were already working with mocap and game engines in a certain way. I had a background in a different game engine, so we kind of changed from Unity to Unreal, which I think was a good choice because we saw that there was more potential, especially in the research projects where we were, where our partners were using the same things.

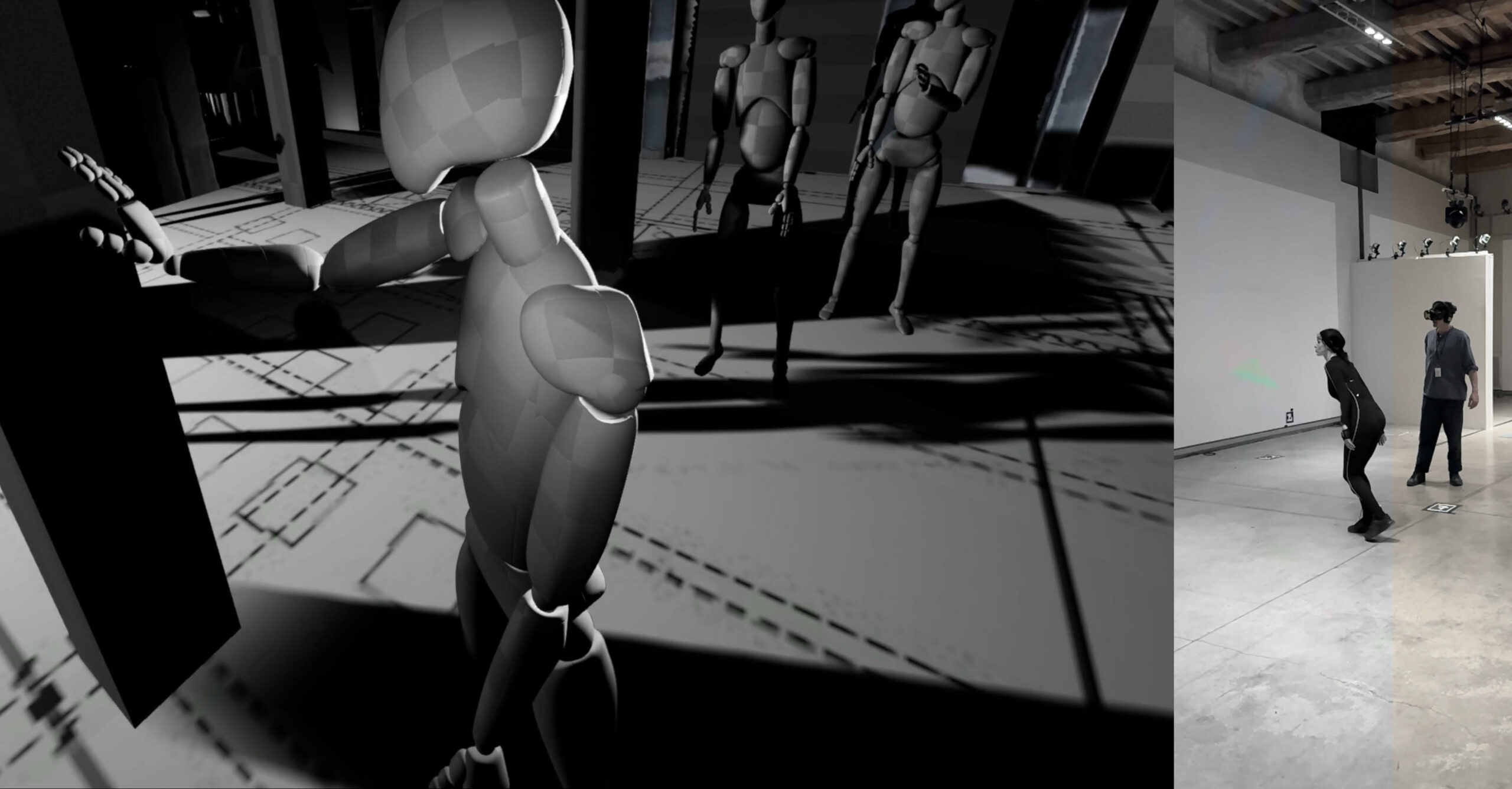

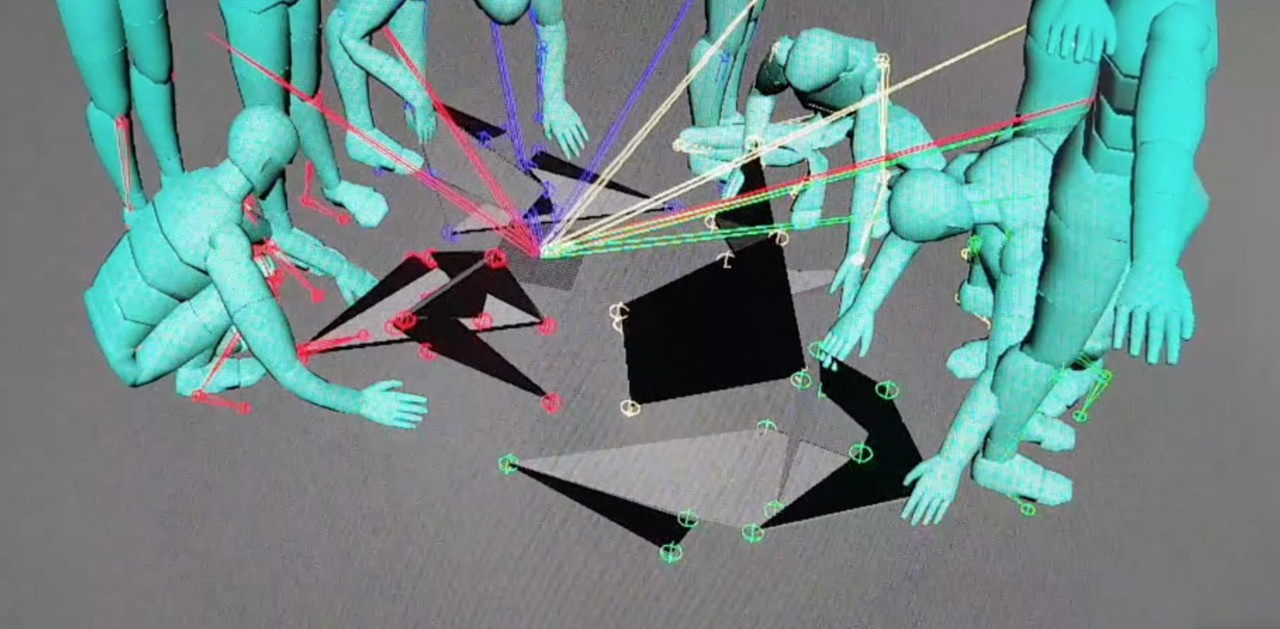

A big step was to change from optical mocap to inertial mocap, because we want to do things on large areas and with optical mocap, you were always limited to a smaller volume because you need to have cameras around. If you were in inertial mocap suits, you could walk around more freely in different types of spaces. This gave us a much larger surface to work on. And then we work with Unreal Engine, mainly because for artists it has a bit more tools than Unity. We also work a lot with 3D scans that we process. I personally work a lot with Houdini for 3D modeling, procedural modeling. Haryo uses more Blender. And we have our own pipeline of working with things. We also use tracked objects (Vive trackers + custom ones from UHasselt). Now we’re using different types of ways to render things over Wi-Fi. For us, the idea is that we kind of make a machine, like a rig that we can adapt to spaces. And in these types of spaces we can start making our performances.

We’re always checking the latest updates of different things to see if we can do new things, which makes it quite challenging. There was a time where we had to have lots of things developed specifically for us but now we can work more with tools that are available because there is an industrial push. But we also noticed that you’re still tied to these companies which have a certain commercial (or privacy) policy which can be very limiting sometimes. I mean, if it exists in the industry: we use it. If we have to invent our own stuff, we try to do that in collaboration with our partners in the EU research projects such as PRESENT, MAX-R; or EMIL in which we are now.

Eric Joris: To add to that, the tools we like most are those that take us into a shared live and embodied experience where they can empower the actor, the performer, and in a very near future the audiences.

Isjtar Vandebroeck: A very important thing which we also noticed is that; when I was in Zagreb for the Realities In Transition – XR Camp in Kontejner, there were a lot of young and emerging artists. I think it’s very important from a technological artistic point of view: I don’t think you should just look at what exists and try to do things with it. You should try to develop a technological vision and try to engage things that already exist, but also try to develop new things and new directions and not just follow the flow of what is going on in a way.

C.D.: About Letta’s residency now: what tools, insights, methods were you able to share with her to go further on her project?

Haryo Sukmawanto: As Isjtar was saying earlier, we are working with lots of these technologies like motion capture and Unreal Engine, which Letta also uses but in a different way. And that was really interesting to see how she utilizes those tools. For instance, with motion capture, where we would want to have a higher fidelity; she was using more of the destructive inaccuracies of her motion capture suit and how to incorporate that into her experience… We were going for full immersion; she was using Unreal Engine almost from a gamer background like with Twitch streams and stuff like that. So it was nice to see how we have the same routes, same roads, but different paths.

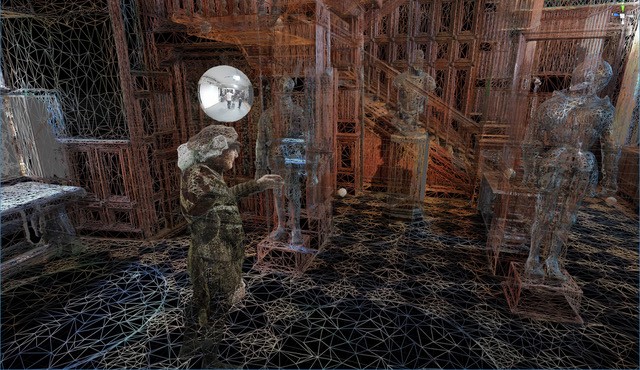

Isjtar Vandebroeck: She had an historical scan of an archeological site in Malta that she was struggling with. As we have a lot of experience with 3D scanning (Leica BKL360, Lidar), we could help her a bit on how to optimize it for her to actually use it because she couldn’t use it before. She was very limited by her computing power. We have powerful computers so she could try new stuff, work faster, which I think helped in her to speed up the creative process and to reduce a bit the friction of what you want to do and how you can do it.

C.D.: Would you have any advice for a collective or an artist who would start with XR?

Isjtar Vandebroeck: It certainly cannot be an easy thing for young artists, you need to acquire tools and skills, it requires time and money. I studied film in a country without a film industry. How can you possibly develop a film language if you cannot practice all the time, like a painter or a writer does? VR is complex by nature. You might not be a technological or digital mind, but be very good artistically. So how to bring everything together? Which is why we built CREW a few decades ago. For a while we were dreaming of building an infrastructure, based on our vision for Large Area VR, an environment that we could share with and introduce to other artists. We are still pursuing that dream.

What many artists naturally do is to abuse the technology in a way that it was not necessarily intended. I think that’s a very good way of approaching it. Otherwise, it’s a real challenge because for example, there’s a real problem right now, I think in VR artworks it’s that very often people are alone, it’s very labor intensive, it’s also too expensive in terms of equipment and it’s hard for people to make something which kind of goes further than the first stages. There’s quite many exhibitions of very simple artworks where you can touch something and see something. But I think it’s good if artists work together to make something which is a bit more sprawling, a bit bigger, to see if we can push the medium; more looking towards the fringes and not just use it as some kind of, “oh, this is just an audiovisual experience”.

Eric Joris: Yeah, it certainly is not easy for young artists because you need to acquire skills, you need to carry maturity by doing a lot of things. I studied film in the past and in Belgium there is no film industry. Everybody was dreaming of making movies. But then how can you if you cannot work every day or every month and use the material… You can only look for a budget, and then once every seven years you are able to make your thing. How can you possibly be a good filmmaker if you cannot practice all the time? If you would be drawing, you need to practice all the time, you need to work, you need to be confronted all the time. In VR it is very complex by nature. How can you handle all that? You might not be a technological or digital mind, but very good artistic or whatever. So how do you bring all that together? In the performing arts, you have a structure. Then you have a composition, you work with people together and that’s a solution. But the individual artists in a world that is not easy to enter in terms of “how do you survive? who do you sell your work to?”, I think it must be very difficult in the beginning, so there must be a space where people can act and meet. For a while we were dreaming of building that environment based on a large area type of thing, where other people could work. But at the moment it’s still kind of a dream.

C.D.: But I guess residencies create these kinds of spaces…

Isjtar Vandebroeck: Right! It’s also good that since a couple of years now, the separation between who’s artistic and who’s technological has become less clear. For example, Letta, she was very independent in her way of working. There’s a thing in VR that when people start, they kind of have the wrong conception of what it is. So they start working and usually they get a bit lost because they’re trying to apply concepts of film or different types of ideas that they have of what it’s supposed to be. This idea that Eric mentions of total reality illusion which doesn’t work. But it’s also kind of good that people already have some basis to work on so they’re quite independent in a way. They can work and we just help them out by talking about their concept. I don’t think the word mentorship is really accurate. It’s more like a guiding partnership or something like that. We were not telling her what to do. She does it all by herself.

Eric Joris: Unlike in other arts there is yet no standard as to what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ XR. Which is a luxury situation: the medium is still kind of open in many respects, while curators seem to borrow artistic standards and needs from cinema, from visual arts, from gaming…

C.D. : Where do you imagine VR going?

Isjtar Vandebroeck: There’s definitely a push towards multi-user experiences that we see in industry. Unfortunately, right now the budgets are mostly reserved for more commercial works, but I think that there’s definitely a better direction than playing golf at home on a Quest headset. The good thing about the term XR is that it becomes easier to explain that you’re working with different media at the same time. So this, I think, is a good evolution in a way. Otherwise I don’t really know. There’s all these hype cycles and everything, but we kind of ignore them. We just work on our thing in a steady manner. But we’re happy when there’s a bit of hype because it delivers some technological advances which have in VR consistently come slower than expected.

Eric Joris: I think the collaborative, the online and the large area concepts in embodied VR remain most interesting and promising. Our large area concept and development of live tools are meant to be an answer to this. Extending VR, or see VR rather as part of a chain of other media and information also seems to be a logical next step towards a wider use and implementation. In niche markets VR will become ever more useful, even become a need.

It will take a while though before VR becomes a consumer type of article.There is still so much room for experimentation, for uncovering unknown usecases and experiences. In arts we should be leading this exploration, rather than waiting for the industry to deliver us the tools or formats.

Isjtar Vandebroeck: There is the technical advancement that we’re kind of waiting on. I mean, we’re trying to push to get there, but it’s quite hard. It’s that we’re trying to make some type of porosity between the different realities. First of all, having a body in VR when you’re wearing the headset is still a problem that is not completely solved. There are solutions for it but they tend to be kind of weird. It takes a lot of your space, you can’t really work on anything else. This is then the subject of what you’re doing. This is an area which is advancing but which is not there yet.

Another thing is we would like to see if it’s possible with some kind of mocap or whatever to have the audience having some presence to people wearing a headset so that the barriers become more fluid and we can start working again on how can we work with this friction between the different realities in an interesting way. There are a lot of advances in this area right now, which are until now too expensive for us to use. But they have a lot of potential artistically, I think, of really developing this idea of XR to more than just a term which brings things together, but really as a concept of “how can you you tell this with this”, but maybe that interacts with that and you get all these different layers that get stacked in a way which I think is artistically very interesting…

C. D.: To conclude, what are your main inspirations? If you have books, movies, video games or whatever that inspired you in conceptualizing XR? And also where do you keep getting more inspirations?

Isjtar Vandebroeck: We actually have a running joke inside CREW with one of our actors. Every time we put on the headset, he says “Do you know the film The Matrix?” (Laughs)(…).

I’m a big fan of science fiction. I read a lot of science fiction, but also science fiction like J. G. Ballard and things like this. But we try to make our work not too sciencefictionny because it very easily becomes a cliche and you’re immediately in the video game aesthetic. This is something we avoid, even if I love video games, for example, Death Stranding is a big inspiration for me. Different types of things: Stalker by Tarkovsky, Hellraiser by Clive Barker, Ghost in the Shell, The Atrocity Exhibition by J. G. Ballard, Journey, a very emotionally bonding videogame, Titane by Julia Ducourneau, Cronenberg, Junji Ito, etcetera.).

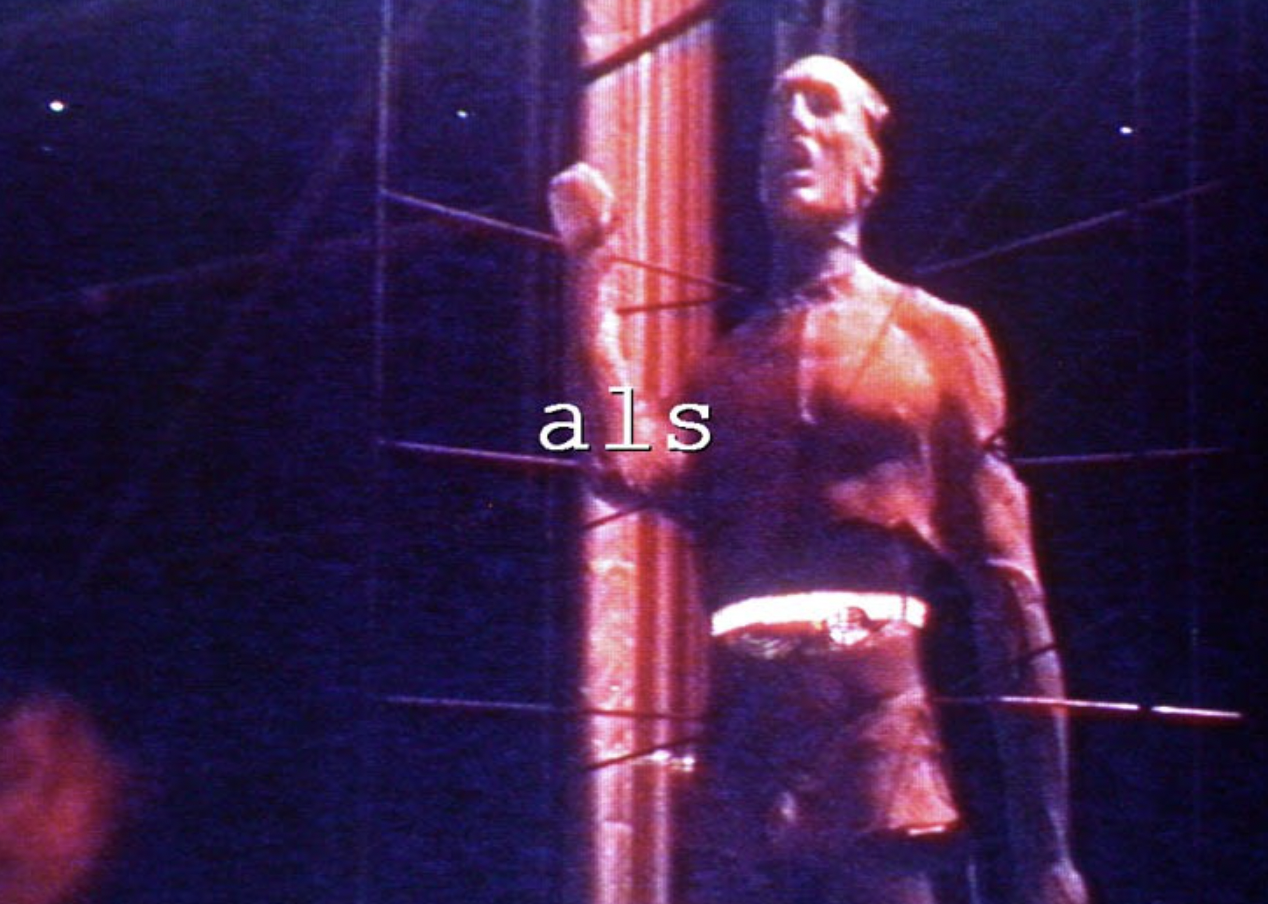

Eric Joris: Eyeopeners for me were the performances of the Japanese Dumb Type collective in the nineties, the work of Stelarc, the videos of Matthew Barney and more recently those of Laure Prouvost. In literature, Carlo Rovelli and Alva Noë are of inspiration.

I just read an interesting reflection on ‘Peer Gynt’ of Hendrik Ibsen. The play was beyond the capacities of the theater of the day: the sequences of images in language and visual composition became technically only possible in the later medium of cinema. With that observation in mind: which present movies, games, performances would we pick that go beyond the capacities of their medium and in fact should use XR?

(…)

Anyway you need to have a good view of what’s happening around you in terms of books, movies, and all kinds of things. But that is not leading us in a direct way to making something. It’s rather: “oh, can we use this or that”. But if you are looking for things that could have been inspiring or that were really worthwhile for me, another one I would name is La Jetée of Chris Marker (…)

Isjtar Vandebroeck: I think there’s another film which is very important to us. It’s not a film that I’m particularly fond of, but it’s very illustrative of some of the concepts that we work on, which is Inception (Christopher Nolan). I think this is a film which has influenced us because it works also with different layers of immersion that interact. For me personally, when I saw this movie, it also made me want to create worlds…

Eric Joris: We used the example of ‘Inception’ during a 2011 CVMP conference with a slightly provocative claim that we would rather DO what Inception is about than TELL its story. With our ‘headswap’ configuration at that moment we could indeed ‘engineer reality’.

In fact, if you look at our daily use of technology and media from a distance it is clear that our whole reality is already very much layered. It is what Ballard called “the science fiction of the present day”.

(…)

Our whole reality is already layered. It’s already a science fiction type of reality.

C. D.: A huge thank you for this very philosophical discussion on realities… I’m heading to consume some science fiction right now.